A Lot of Things I learned from False Dawn, Part 1

Summarizing the Groundwork

Over the past few weeks, I have read George Selgin’s 2025 book False Dawn. The 384-page book is a deep dive into how the US recovered from the Great Depression and what role, if any, the New Deal played in that recovery (the book does not cover the other two R’s, relief or reform). In fact, according to Selgin, this is the first book focused on these two questions.

It’s a remarkable piece of work. The book is dense, meticulously researched, and relentlessly informative—hardly a page passes without an unfamiliar fact or a revisionist insight. Because there’s so much here, I’ll be splitting my discussion into three posts, one for each major section: “Groundwork”, “The New Deal’, and “After the New Deal”.

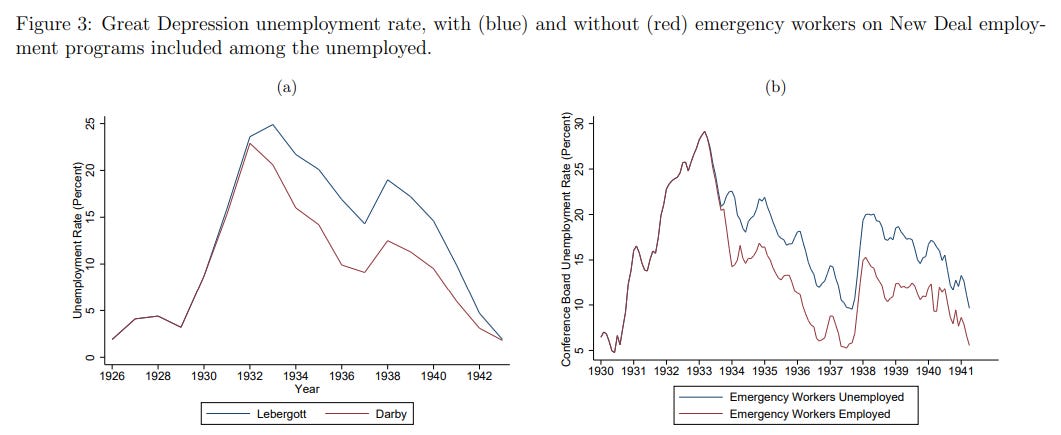

There are two methods to measure unemployment during the Great Depression-- the BLS’s methodology and Michael Darby’s revision. The standard BLS methodology treats New Deal workers as unemployed, while economist Darby’s method counts them as employed. Both tell the same basic story: the U.S. remained mired in double-digit unemployment through 1940—about 15% under the BLS measure, and 10% under Darby’s.

While Darby’s measure does paint a brighter picture for the New Deal, its methodology is at odds with the New Deal’s own recovery goals. The Roosevelt administration never intended to replace private jobs with government work programs. To quote Roosevelt, the goal was not to encourage “the rejection of opportunities for private employment or the leaving of private employment to engage in Government work”. Their government employment was only a temporary measure until “such time as private employment is available.”

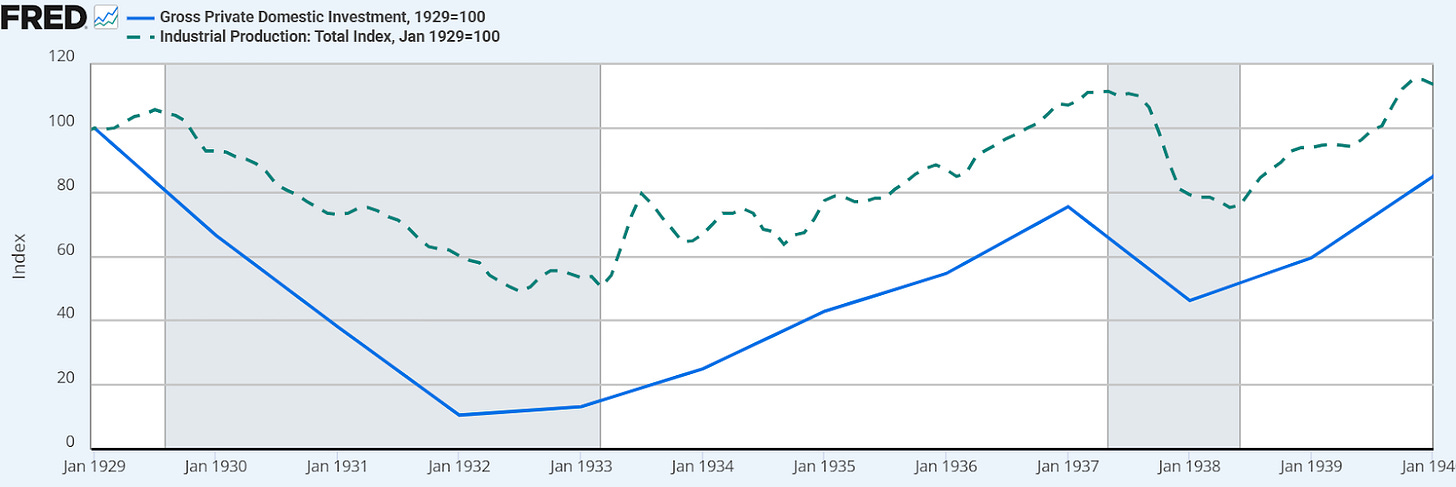

Gross Private Domestic Investment was still 10% below its 1929 level by 1940, and industrial production had only grown 12%. As mentioned above, unemployment was still in the double digits by either measure chosen.

Key figures like Raymond Moley, Frances Perkins, and Rexford Tugwell all stated there was no New Deal plan during the 1932 election. While FDR did call for “bold, persistent experimentation… above all, try something”, that something was rarely defined. His nomination acceptance speech only took clear positions on prohibition and agricultural mortgages.

The 1932 Democratic platform had more details, but what it did include often went against what was implemented as part of the New Deal. For example: a reduction in government spending, balanced budgets, a sound currency, and antitrust enforcement. To the extent the platform did foreshadow the New Deal, those planks were squarely focused on relief and reform (for example, Social Security).

By February 7, 1932, the US was two weeks from either defaulting on foreign obligations or violating the Federal Reserve’s gold reserve requirements. This led to the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, which allowed Federal Reserve Notes to be backed by Treasury Securities.

There were over 30,000 American banks in 1920. This was up from 12,000 in 1900. Before the Great Depression began, thousands of US banks failed during the 1920s due to falling crop prices, and thousands more failed once the Great Depression began. In Canada, only 18 banks failed in the 1920s, and none failed during the Great Depression.

US bank failures initially began with rural banks, but spread to urban banks. By January 1933, the crisis reached Detroit, whose banking industry was concentrated around Ford Motor Company. On February 15th, Michigan’s Governor declared a banking holiday-- spooking other governors. By March 3rd, nearly half the states had closed their banks. By the time FDR declared a national banking holiday on March 6th, most states had already taken the same measure. FDR acted more so to prevent other countries from withdrawing gold from the US.

Herbert Hoover considered declaring a national banking holiday himself in 1932. His Treasury Department even drafted an order for Hoover to sign, but opted not to do so due to concerns about its legality and Congress’s support. To address the latter issue, Hoover attempted to get FDR’s support.

When FDR signed the bank holiday Executive Order, it was with the support of Hoover’s Treasury team. Selgin described FDR’s national bank holiday as “the Hoover administration’s swan song.”

Czechoslovakia established the first national deposit insurance scheme in 1924. New York State was the first US deposit insurance scheme in 1829.

Speaking of deposit insurance, it was a rival reform to branch banking. In Congress, Henry Steagall was a branch banking opponent and deposit insurance proponent, while Carter Glass was a branch banking proponent and deposit insurance opponet. Glass eventually threw his support behind deposit insurance to get Steagall’s backing for separating commercial and investment banking.

Like Glass, FDR opposed deposit insurance and even threatened to veto the entire 1933 Banking Act. FDR eventually withdrew his veto threat because Congress had enough votes to override it.

While I agree with Glass on branch banking, his position on investment banking is less agreeable. In Congressional hearings, Glass offered a single example to justify the commercial-investment split, the Bank of the United States. Incredibly, his own example bank did not deal in securities.

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) initially provided liquidity to banks through loans, but its responsibilities were eventually expanded to provide capital to otherwise unsound banks after they reopened following the national banking holiday. Its responsibilities further expanded when it began to offer loans to private non-bank businesses.

Contrary to popular narratives, the Hoover administration did not take a hands-off approach to the Great Depression. As mentioned above, FDR’s national banking holiday was based on a Hoover administration plan and implemented by Hoover’s Treasury team. Arthur Ballantine, Hoover’s Undersecretary of the Treasury, was even offered the opportunity to serve within FDR’s administration.

On public works, Hoover’s administration spent more than the previous nine administrations combined, which included Panama Canal construction.

“We might have done nothing… Instead, we met the situation with… the most gigantic programs of economic defense and counterattack ever evolved in the history of the Republic.” -Herbert Hoover in 1932

On March 8, 1933, the Fed began compiling a list of people who had withdrawn gold from the Federal Reserve Banks or their member banks, but had not returned it.

Selgin on Twitter: “In fact Hitler started helping the U.S. to recover in 1933, when he became Chancellor. From then on European war jitters caused a massive flow of gold from there to the U.S., where it contributed far more to U.S. recovery than any deliberate New Deal fiscal or monetary actions.”